The complete issue

Vol. VIII, No. 1

(32 pages)

Print edition: Visit our store to check availability

Digital edition: Visit JSTOR.org to purchase

Subscribe to MI

Explore the MI Archives: Browse | Advanced search | Tutorial

Inside

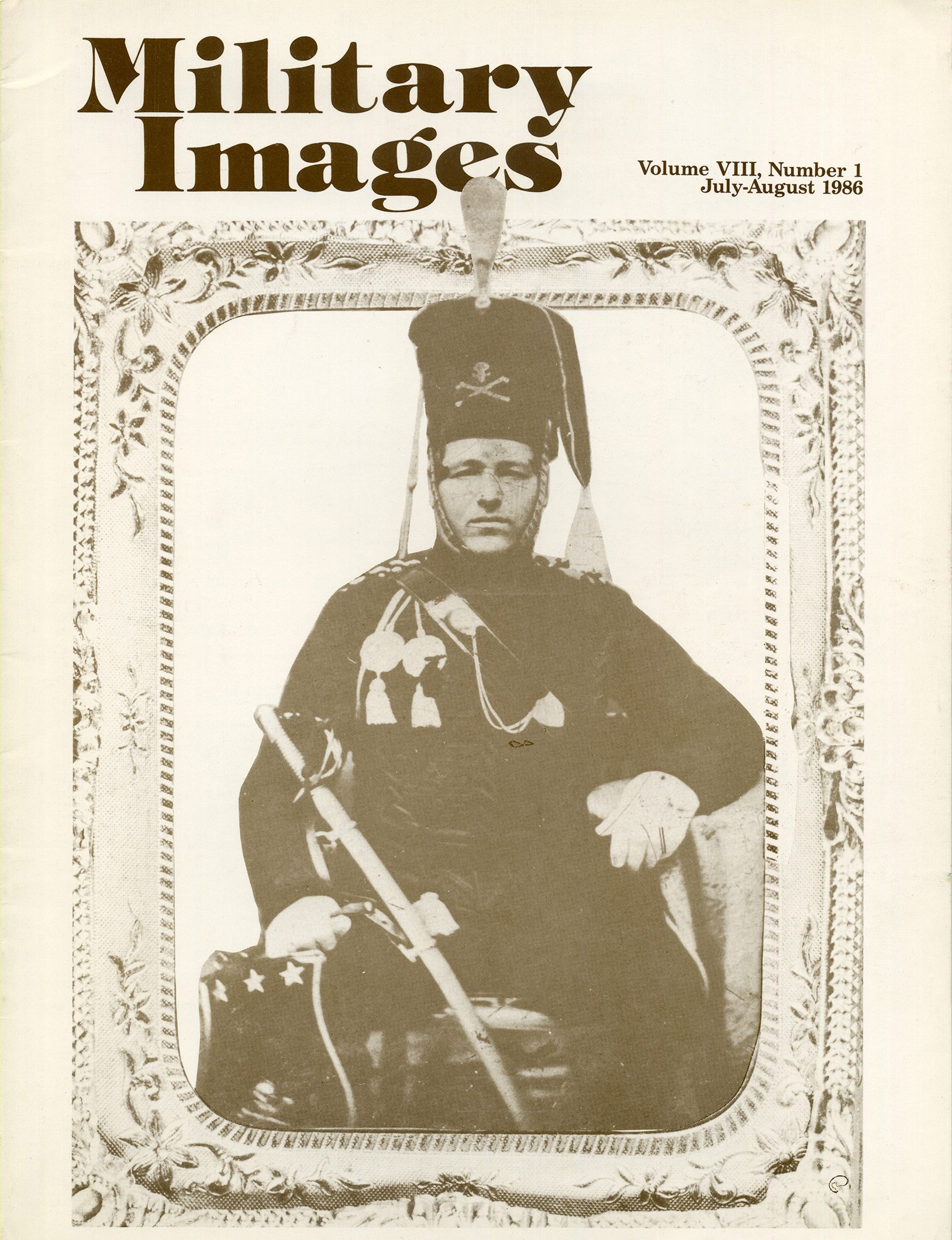

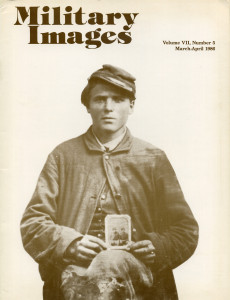

Cover image

The cover of the current issue is an American hussar from about 1860, complete with the fur headgear with the death’s head insignia.

Editor’s Desk (p. 1)

The editor discusses the problem that the publication team had with saving and using back issues of Military Images. He writes with high praise for the work of Frank Jasek, who bound each volume into a hardcover set. The editor also discussed some of the upcoming features planned for future issues.

Mail Call (pp. 2-3)

A lengthy letter from a reader questions the identification of an individual in as Lt. David Raney, Confederate States Marines, providing a great deal of information to put the positive identification back into question. Another article disputes the assertion that the Colt revolving rifle saw limited and unpopular use during the war, using the history of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade as evidence.

Passing in Review (pp. 3-4)

Four volumes are presented for review in this issue of Military Images. First is Recollections of a Naval Officer by Captain William H. Parker, which is a quality reprint of the memoirs of a Confederate naval officer who had many memorable experiences; it is reprinted as part of the Classics in Naval Literature series. Next is Soldiers: A History of Men in Battle by John Keegan and Richard Holmes. The volume is a companion book to a British television series and devotes considerable space to discussions of the American Civil War and the lessons that were “too often ignored by professional soldiers in Europe.” Third is History of the First Delaware Volunteers by William P. Seville, another reprint of the original and only history of the unit written in 1884. Last is a review of an audiotape, Battlefields and Campfires, by the 97th Regimental String Band. Created by reenactors. The tape includes many of the songs of the era, played as they would have likely been played by soldiers of the Civil War.

The Darkroom (p. 5)

George Hart answers a question from a reader regarding the best way to repair damaged daguerreotype cases and how collectors store or clean their images. He responds with a list of products and suggested reading, and also explains that the means used by museums to control the environments of their collections are beyond the means of collectors. He describes how a pistol case can be used to protect images that are within cases and also cautions collectors to use “acid free” products that might come into contact with albumen images in particular.

Izzat a Chaplain or what?: Masonic Uniforms of the Civil War Period by Jacques Noel Jacobsen, Jr. (pp. 6-7)

A part of American history that goes back to before the Revolution, the fact that there were organized military lodges of Masons among both Union and Confederate soldiers should come as no surprise. The story is frequently told of captured or wounded Masons giving the sign of distress to their captors in order to receive protection while captured during the Civil War. What is more unusual is to see some of the Masonic badges and symbols from this era. The article includes six different images which describe the insignia, from the simple Masonic square and compass to the more elaborate insignia worn by Knights Templar and even a Master Mason. Two images from the post-Civil War era are also included.

Corps Badges of the Civil War, Part II: VI through X Corps by Wendell Lang (pp. 8-15)

The second of the series on the Corps badges worn by Federal soldiers begins with a short description of how the felt insignia were supposed to be worn, which was on the front or top of the cap, or the side of wide-brimmed hat. As seen by the images included in the article, the men had other ways of wearing their corps badges. Often purchasing more elaborate pins or even cockades, the men would also wear their badges with pride on their chest. One image shows a private of the 10th Vermont Infantry wearing the badges of both III and VI Corps, along with another shield-shaped badge, showing the movement of units between corps. The article shows thirteen soldiers wearing the VI Corps badge, a vertical Greek or Swiss cross, in a number of forms. There was no badge adopted for VII Corps (the Department of Arkansas) during the war, but a five-pointed star riding on a crescent was approved after the war was over and before the corps was disbanded; no photographic image is included. VIII Corps also had no official corps badge, but the men adopted the six-pointed star, as shown in the image included with the article. The badge for IX Corps was a badge shape with cannon and anchor imposed on it, reflecting the “amphibious operations” of this corps in North Carolina at the start of the war. The last badge presented in the article is for X Corps, a “square with an extended point at each corner” which represents the overhead view of a typical fort “with four bastions.”

The Militia of ’61: U.S. Army Uniforms of the Civil War, Part VIII by Michael J. McAfee (pp. 16-24)

Providing an overview of the history of militia in the United States, the author intends to show that there was no one “militia” in existence at the time of the Civil War. Tracing back to the “common” militia under which the different states could design their own militia system, the reader finds out that this system was in great decline by 1861. However, the “volunteer” militia, which were basically private clubs that were attached to the “common” militia. By the decade prior to the Civil War, states such as Massachusetts and New York tried to instill a regimental spirit by imposing uniforms, but this was largely unsuccessful, as the competitive nature of these groups prevailed. To make things more complicated for the collector, there were also units that had a military air to them, but were not actual militia units. They were more of a social club, many of which would perform as drill or marching societies. Militia uniforms could take three forms: “modern” units would wear variations of the 1851 U.S. Regular Army uniform; “traditional” units would wear the older type of uniform with high collars, tight sleeves, and tailed coats; “specialized” units would have more elaborate uniforms and could include hussars, Highlanders, and Zouaves. The twenty images that accompany the article, including one of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Butler of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia in 1861, provide an excellent visual overview of the discussion.

“Up, Alabamians!”: The 4th Alabama Infantry at Manassas by Gregory Starbuck (pp. 25-29)

Eleven images of the men of the 4th Alabama illustrate the account of the first engagement that this unit underwent. Under the command of General Bernard Bee on Henry House Hill , the unit lost 40 killed and 170 wounded. The article recounts the stories of those who survived, such as Private Joe Angell who was knocked unconscious by a cannonball that hit his knapsack, and those who did not, like Colonel Egbert Jones who had undergone the embarrassment of a petition by his men because they had not seen enough action and wanted to redeem himself in battle. It also includes the story of two men who were not supposed to be there. Dr. Samuel Vaughn had been visiting relatives in the 4th when the unit moved out to Manassas from Winchester; he and his servant, James Jefferson (one of the few documented cases of a slave fighting for the Confederacy), accompanied the unit and fought with the regiment in this first frightening step into the Civil War.

Stragglers (p. 30)

Two images—a “before” and “after” pair—show the crew of a ship identified only by a banner in the second image with “O.Y.C.” The first image shows the crew cleaning up for their photograph, wearing undershirts and getting shaved, brushing hair and teeth, and generally in a relaxed mood. The second image shows the same crew with their banner and American flag, posing for their photograph in uniform and looking “shipshape.”

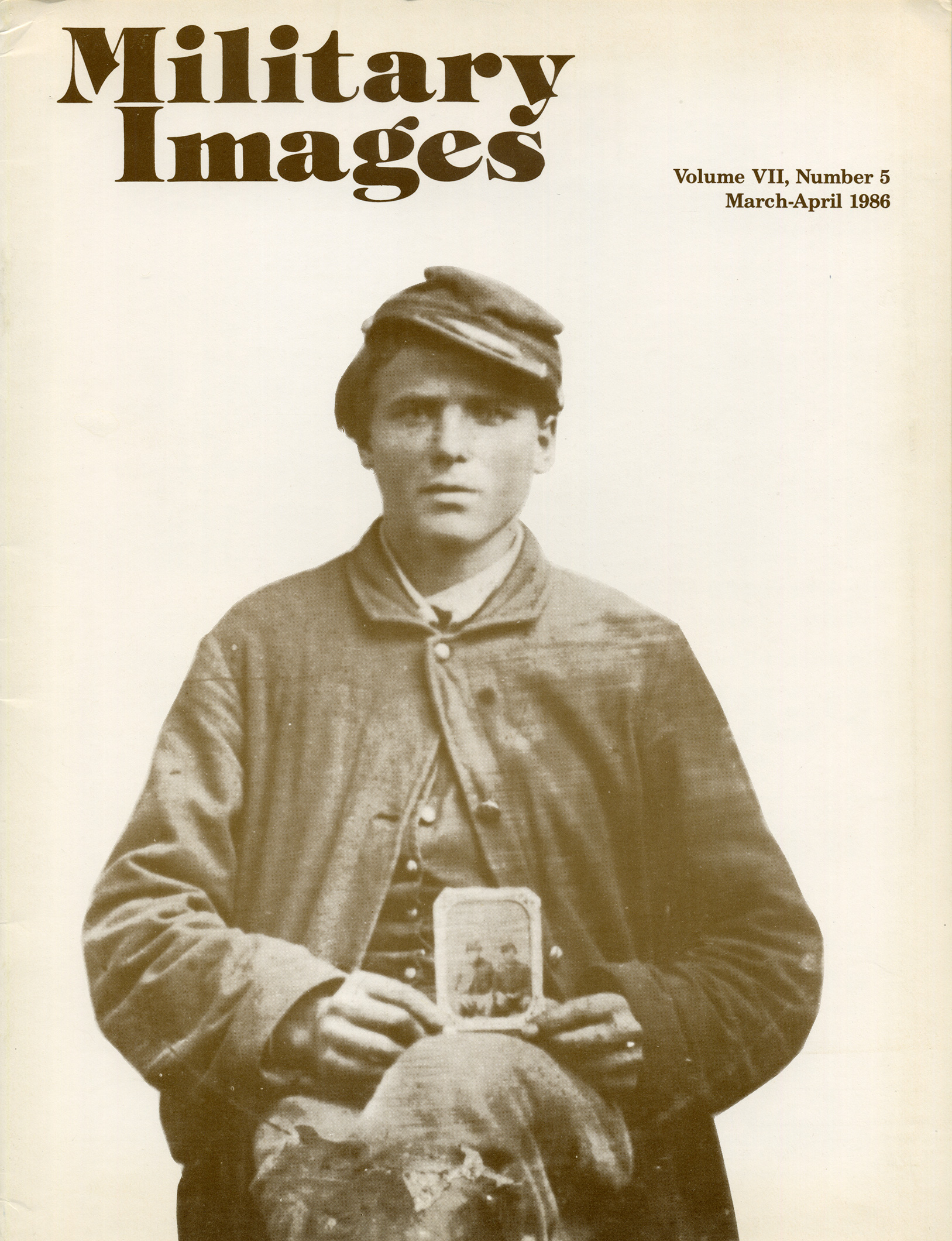

Back Image

1st Lt. James Young of Company K, 4th Alabama who was involved in the fighting of the 4th Alabama at First Manassas.